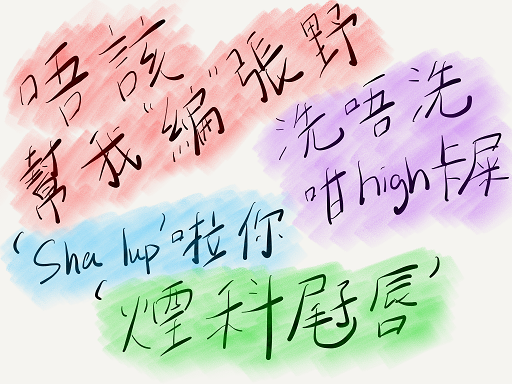

When foreigners come to Hong Kong and hear us talk in our mother tongue language Cantonese in a style that is mixed with English (known as “code-mixing“), it often gives people the impression that we are international citizens who are quite used to using English in our daily lives. But at the same time, people tend to question whether this conversation style is a good or a bad habit, as it is often seen as a way to raise one’s social status more than anything else. Recently, I have read a few ‘rant articles’ on the internet regarding code-mixing: one written by a mainland Chinese person and the other by a Taiwanese person, who have both expressed their utter dissatisfaction at the use of code-mixing by a Hong Kong person and a Taiwanese person respectively. This made me reflect on myself, as I am also a native Hong Kong person who attained quite a habit of code-mixing from studying overseas in Canada. So I asked myself, “Is code-mixing really that bad and inappropriate? And if it drives people nuts, should I stop talking in this style? Because to be honest, I really don’t mix English words into my Cantonese conversation for the sake of raising my social status, but I have just gotten used to this talking style for a long time, as if this habit of code-mixing was in my blood since I was born!”

Perhaps the first thing that we should do before we make a real judgement on someone is to identify the intention behind their use of language. But when it comes to doing such a thing, it can be extremely difficult because we may have already formed a stereotypical image of a person from their language community in our own minds, based on our past experiences. In addition, it is very easy for us by human nature to make generalisations, whether they’re of things or people, especially when our past experiences were unpleasant. At times, we may even manifest our feelings and thoughts solely based on those past experiences, which can lead to a whole language community being mocked or even discriminated. As a result, the entire language community can take a hit in reputation if we spread the word to others, and those other people may spread the word to even more people, and so on. But as we are living in year 2020 where the world has become vastly globalised compared to just a few decades ago, can we now say that we can make a fair judgement on a person solely based their language spoken?

In a place like Hong Kong where it’s famously known as an international finance centre with an influx of foreigners all the time, it makes a lot of sense that we native Hong Kongers have adopted so much foreign vocabulary in our local language, as we are very used to accommodating to speakers of other languages during a conversation. However, it is interesting to see that our daily primary language of use is still Cantonese, even though our official languages are both Cantonese and English. If we look at the government statistics, we can see that there is still about 88% of the population in Hong Kong that speaks Cantonese, which means that the culture of Hong Kong still primarily revolves around the Cantonese language. Yet, compared to the other Asian communities nearby Hong Kong, we tend to be a lot more open-minded on the habit of code-mixing in our daily conversation, which one could say is related to our overall English proficiencies being higher than average. But the question is, why do people have such a negative impression of code-mixing?

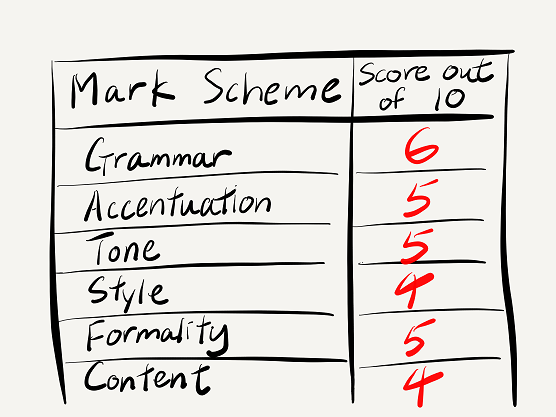

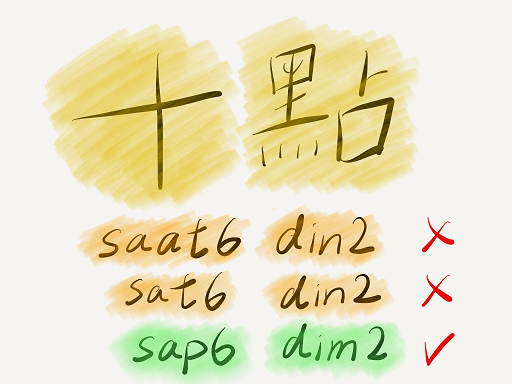

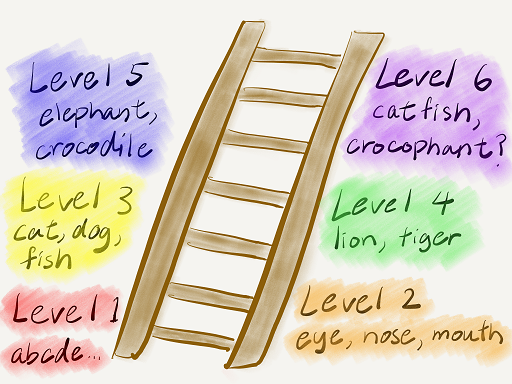

In an article that I have previously written here, I have mentioned that it takes a lot more skill to code-mix than it is to utter loan words in one’s mother tongue language, as code-mixing in the strictest sense involves correct pronunication of foreign words, which requires adequate cultural literacy in a foreign language. But the thing is, as code-mixing is a mixture of two entirely different languages, can one say that code-mixing could be a legitimate kind of language, especially if there are no rules and constraints involved? Interestingly enough, I have recently gathered evidence of possible explanations behind code-mixing usages of Hong Kong Cantonese in my Hong Kong Code-mixing Dictionary project here. Furthermore, code-mixing terms in Hong Kong Cantonese have already long existed back in the colonial days from our past generation, as terms such as ‘auntie’ or ‘uncle’ are ones that a person must know in order to show respect for someone that they have just met (not even for a person who doesn’t speak Cantonese!), especially when the other person is more senior and of higher authority. Nonetheless, the most important question boils down to: should we allow this habit of code-mixing to continue or cease for the future development of Hong Kong Cantonese? This, I would say, is at the heart of whether code-mixing can become a form of language that can be appreciated, as different people may have different opinions on how language should be developed based on their own past experiences, cultural upbringing, education background, etc.